The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was a key battleground in the U.S. government's campaign to erase Native American cultures and identities through forced assimilation. From 1879 to 1918, over 7,800 students from over 100 tribes were confined within its walls, enduring harsh conditions, loss of language and culture, and, in many cases, death.

Two of these children, Matavito Horse, a Cheyenne boy, and Leah Road Traveler, an Arapaho girl, both perished shortly after their arrival in 1879. After a long battle by their respective tribes, the remains of 17 children were returned to their homelands, where they were ceremoniously reburied in a tribal cemetery in Concho, Oklahoma, last month.

This act of repatriation was celebrated as a crucial step towards healing and justice for the communities affected by the stark legacy of the boarding school system. According to tribal leaders, these ceremonies help restore dignity to the memories of the children's experiences and provide a much-needed closure to families that have spent generations seeking answers.

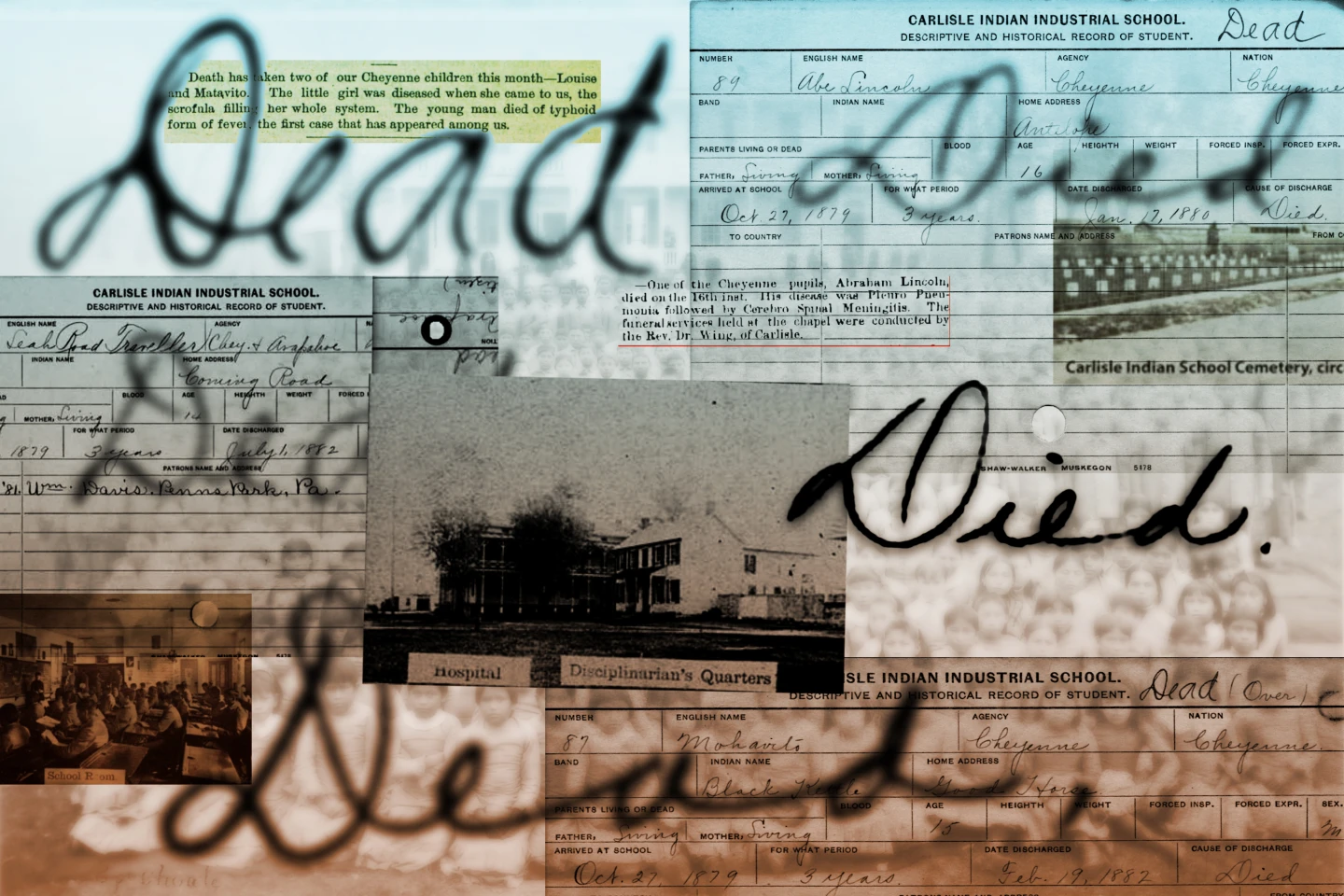

Federal records have revealed that many of these children died due to diseases such as tuberculosis, spinal meningitis, and typhoid fever, but the documentation often lacked essential details like names or family connections. Preston McBride, a historian at Pomona College, remarked that sometimes the only memory left of these children is a single slip of paper with scant details about their lives.

More than 973 Native American children have been documented to have died in U.S. boarding schools, marking a dark phase in American history filled with pain and suffering. The recent efforts towards repatriation and acknowledgment of these students’ lives have led to national conversations about reparations and the responsibilities of the federal government toward Native American tribes.

Norene Starr, a Cheyenne and Arapaho representative involved in the repatriation efforts, pointed out the continuing challenges faced as they work to identify additional remains at various boarding school cemeteries across the country. It's a complex and costly process requiring significant moral and financial support from both the federal government and church entities implicated in the historical injustices.

This moment in history encapsulates the strength and resilience of Indigenous communities as they move towards reclaiming not only their ancestors but also their cultural identity.