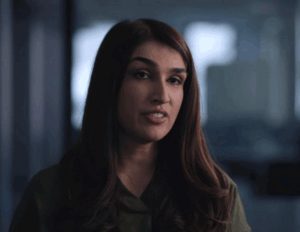

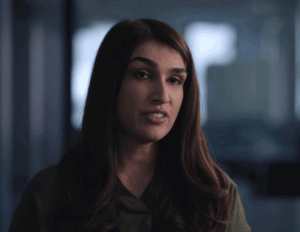

When Keira's daughter was born last November, she was given two hours with her before the baby was taken into care.

Right when she came out, I started counting the minutes, Keira, 39, recalls. I kept looking at the clock to see how long we had.

When the moment came for Zammi to be taken from her arms, Keira says she sobbed uncontrollably, whispering sorry to her baby. It felt like a part of my soul died.

Now Keira is one of many Greenlandic families living on the Danish mainland who are fighting to get their children returned to them after they were removed by social services.

In such cases, babies and children were taken away after parental competency tests - known in Denmark as FKUs - were used to help assess whether they were fit to be parents. In May, the Danish government banned the use of these tests on Greenlandic families after decades of criticism, although they continue to be used on other families in Denmark.

The assessments, which usually take months to complete, are used in complex welfare cases where authorities believe children are at risk of neglect or harm. Defenders of the tests say they offer a more objective method of assessment than the potentially anecdotal and subjective evidence of social workers and other experts. But critics argue they cannot meaningfully predict whether someone will make a good parent.

Greenlanders, who are Danish citizens, often seek opportunities in Denmark, leading to a concern that they are disproportionately affected by these assessments. Reports show they are 5.6 times more likely to have children taken into care compared to Danish parents.

Despite governmental commitments to review cases, many families, like Keira's, remain separated from their children, underlining the urgent need for change in the system.

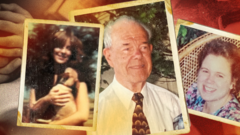

This situation resonates deeply, as parents like Johanne and Ulrik also share their anguish, detailing how their son was taken immediately after birth, while they were denied avenues to adequately contest the parenting assessments that deemed them unfit.

As Keira prepares for Zammi's first birthday, crafting a traditional Greenlandic sleigh, she remains unwavering in her resolve: I will not stop fighting for my children. If I don’t finish this fight, it will be my children’s fight in the future.\

Right when she came out, I started counting the minutes, Keira, 39, recalls. I kept looking at the clock to see how long we had.

When the moment came for Zammi to be taken from her arms, Keira says she sobbed uncontrollably, whispering sorry to her baby. It felt like a part of my soul died.

Now Keira is one of many Greenlandic families living on the Danish mainland who are fighting to get their children returned to them after they were removed by social services.

In such cases, babies and children were taken away after parental competency tests - known in Denmark as FKUs - were used to help assess whether they were fit to be parents. In May, the Danish government banned the use of these tests on Greenlandic families after decades of criticism, although they continue to be used on other families in Denmark.

The assessments, which usually take months to complete, are used in complex welfare cases where authorities believe children are at risk of neglect or harm. Defenders of the tests say they offer a more objective method of assessment than the potentially anecdotal and subjective evidence of social workers and other experts. But critics argue they cannot meaningfully predict whether someone will make a good parent.

Greenlanders, who are Danish citizens, often seek opportunities in Denmark, leading to a concern that they are disproportionately affected by these assessments. Reports show they are 5.6 times more likely to have children taken into care compared to Danish parents.

Despite governmental commitments to review cases, many families, like Keira's, remain separated from their children, underlining the urgent need for change in the system.

This situation resonates deeply, as parents like Johanne and Ulrik also share their anguish, detailing how their son was taken immediately after birth, while they were denied avenues to adequately contest the parenting assessments that deemed them unfit.

As Keira prepares for Zammi's first birthday, crafting a traditional Greenlandic sleigh, she remains unwavering in her resolve: I will not stop fighting for my children. If I don’t finish this fight, it will be my children’s fight in the future.\