With a little over two-thirds of the ballots in the Honduras election tallied, the lead has changed hands.

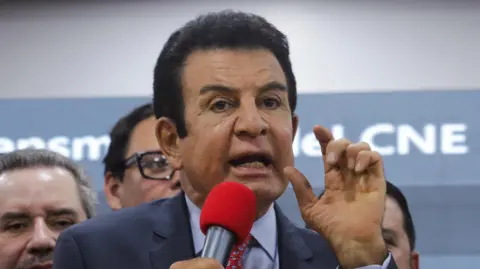

The former vice-president, Salvador Nasralla, has a small but potentially significant lead over his rival, the conservative former mayor of Tegucigalpa, Nasry Asfura. Yet Asfura's National Party continues to brief journalists that they have the numbers for an eventual win.

The race remains on a knife-edge.

In Washington, President Donald Trump has staked his hopes on nothing less than an outright Asfura victory and has tried to directly influence the race in support of his favored candidate.

Whether it has been intimating that funds could be withheld from the impoverished Central American nation or making unsubstantiated allegations of electoral fraud, many in Honduras see the US president's fingerprints all over this election.

To Honduran political analyst, Josué Murillo, it smacks of the kind of treatment Honduras expected from Washington during the Cold War.

No government should come here and treat us as a banana republic. That is a lack of respect, he says in a coffee shop in Tegucigalpa.

Donald Trump saying who we should elect violates our autonomy as a nation, and it affects our elections as well.

Irrespective of whether the National Party go on to victory, one of their key figures is already celebrating.

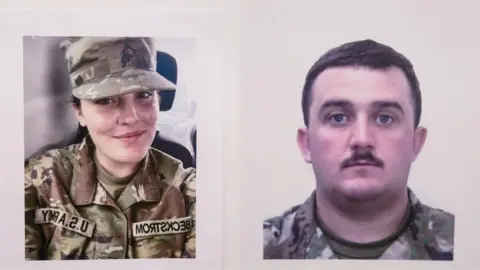

On Monday, ex-President Juan Orlando Hernández walked out of jail in Virginia a free man after serving just one year of a 45-year sentence for drug-smuggling and weapons charges.

His release came after Trump urged Honduran voters to cast their ballots for Asfura. Hernández was unexpectedly pardoned by Trump, despite having been found guilty last year by a court in New York of running a drug conspiracy which had brought more than 400 tonnes of cocaine into the United States.

His time in office had also been marred by allegations of severe human rights violations by the police and security forces, particularly against government critics.

So, when Hernández was arrested in 2022, then extradited to the United States and eventually jailed, most Hondurans celebrated it as a rare moment of justice in a nation riddled with institutional impunity, especially for the political elites.

Trump has claimed the opposite, telling journalists on Air Force One that the people of Honduras really thought (Juan Orlando Hernández) was set up and it was a terrible thing.

His statements reflect an ongoing theme in Honduras where U.S. interference is seen as a threat to national sovereignty and democratic values. Journalists monitoring the situation have expressed concern over the direct influence of foreign powers in domestic elections.

As the vote count in Honduras continues, political analysts speculate on the ramifications of this election outcome, especially regarding U.S.-Honduras relations moving forward.