The United States has pledged $2 billion (£1.5bn) to fund United Nations (UN) humanitarian programmes, but has warned the UN it must 'adapt or die'.

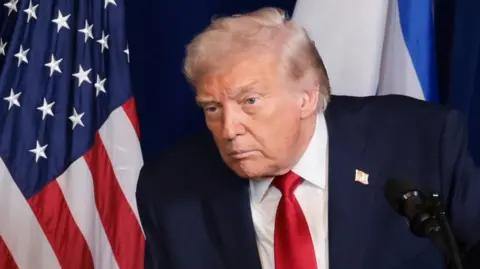

The announcement was made in Geneva by Jeremy Lewin, President Trump's Under Secretary for Foreign Assistance, and the UN's emergency relief chief, Tom Fletcher.

It comes amid huge cuts in US funding for humanitarian operations, and further cuts expected from other donors, such as the UK and Germany.

Mr. Fletcher welcomed the new funds, saying they would save 'millions of lives'. However, $2 billion is a fraction of what the US has traditionally spent on aid; in 2022, its contribution to the UN's humanitarian work was estimated at $17 billion (£12.6bn).

This funding comes with conditions. Although UN donors sometimes earmark specific projects, this US funding prioritizes just 17 countries, including Haiti, Syria, and Sudan. Notably, Afghanistan and Yemen will not receive any money. Mr. Lewin stated that evidence shows UN funds were being diverted to the Taliban in Afghanistan, a situation he indicated President Trump would not tolerate.

Such restrictions pose challenges for aid agencies operating in countries not on the list. Already, funding cuts have resulted in the closure of mother and baby clinics in Afghanistan and reduced food rations for displaced individuals in Sudan. Alarmingly, global child mortality, which had been on the decline, is expected to rise this year.

The US has also stipulated that the new funding cannot be used for projects related to climate change, which Mr. Lewin claims are not 'life saving' and not in US interests.

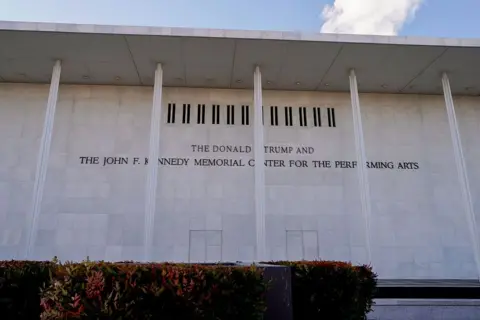

Mr. Lewin, known for his close ties to President Trump, has been instrumental in the overhaul of USAID, including significant staff reductions. He warned the UN that it must adjust to new realities, stating that the US funding mechanisms are less accommodating to traditional aid frameworks.

While Mr. Fletcher and the UN system are eager to welcome any new funding, the politicization of aid—particularly in excluding specific crises or countries—raises ethical questions about the neutrality and impartiality fundamental to humanitarian assistance.

As the UN grapples with extended funding crises and a skeptical donor base in Washington, many will view the $2 billion as a crucial lifeline, albeit one that comes wrapped in contentious strings.