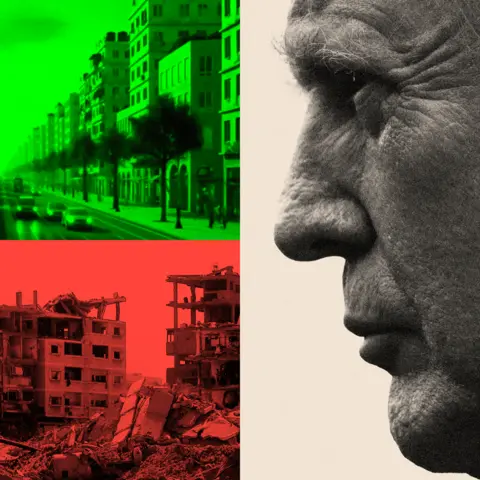

In the midst of a still shaky ceasefire, Gazans are taking the first tentative steps along the long road to recovery. Bulldozers are clearing roads, shovelling the detritus of war into waiting trucks. Mountains of rubble and twisted metal are on either side, the remains of once bustling neighbourhoods. Parts of Gaza City are disfigured beyond recognition.

This was my house, says Abu Iyad Hamdouna, a local resident. He points to a mangled heap of concrete and steel in Sheikh Radwan, recalling how it was once one of Gaza City's most densely populated neighbourhoods. It was here. But there's no house left. Abu Iyad is 63 years old. If Gaza ever rises from the ashes, he doesn't expect to see it rebuilt.

The sheer scale of the challenge is staggering. The UN estimates the cost of damage at £53 billion ($70 billion). Almost 300,000 houses and apartments have been damaged or destroyed, according to the UN's satellite centre Unosat. The Gaza Strip is littered with 60 million tonnes of rubble, mixed in with dangerous unexploded bombs and deceased bodies.

More than 68,000 people have been killed in Gaza during the past two years, according to the territory's Hamas-run health ministry, figures that are accepted by the United Nations and other international bodies. As a result of this destruction, it's challenging to determine where to begin the rebuilding process.

Local populations are sceptical about various reconstruction plans, including foreign ideas like Trump's Gaza Riviera, which they view as disconnected from their needs. In contrast, the Phoenix Plan represents a grassroots approach towards reimagining the city, launched by Gaza's residents themselves. However, many see that the fate of these visions depends heavily on the political landscape and competing international interests.

As local residents sift through the remains of their homes, the future of Gaza hangs in the balance. With urgent needs for basic services like water and viable shelter far outweighing grander reconstruction schemes, the path toward recovery remains fraught with uncertainty and challenge.

In the face of all this, residents like Abu Iyad express a stark reality: After five forced displacements during the war, I just want to stay put, in whatever shelter I can find, or make for myself. Amid aspirations of flourishing, there is still the immediate necessity of survival amidst the rubble.