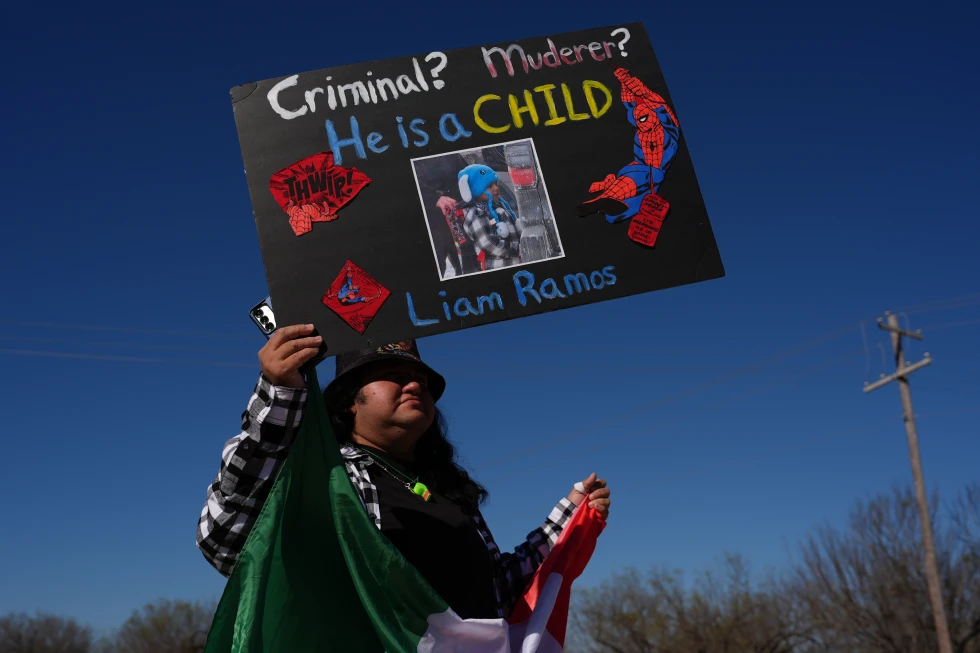

Queensland's government has stirred considerable debate with new legislation allowing children as young as 10 to face adult penalties for serious crimes, such as murder and serious assault. This major policy change, championed by the newly elected Liberal National Party (LNP), aims to respond to public concern over youth crime and promote a sense of safety among citizens. However, critics argue that evidence suggests tougher penalties are unlikely to reduce youth offending rates and may even worsen the situation.

The bills, which the Premier David Crisafulli describes as "adult crime, adult time," outline 13 specific offenses that now carry harsher sentences for minors. These changes include mandatory life sentences for murder, changing the previous maximum of 10 years’ imprisonment, only applicable under extreme circumstances. Furthermore, the laws eliminate previous provisions aimed at detaining minors as a last resort, allowing judges to consider a child's full criminal history during sentencing.

Despite the government’s intentions, multiple studies show a downward trend in youth crime across Queensland, with a record low observed in 2022. Notably, the Australian Bureau of Statistics highlights a consistent halving of youth crime over the past 14 years. The LNP's legislation has been met with backlash from legal experts, child rights advocates, and international organizations, including the United Nations, which argue the changes neglect children's rights and violate international laws.

Members of the Queensland Police Union support the reforms, believing they will improve accountability for serious offenses. However, the new Attorney-General Deb Frecklington has acknowledged that, while necessary, these changes conflict with established international standards. Critics, including the state’s commissioner for children, Anne Hollonds, have condemned this move as an "international embarrassment," emphasizing that contact with the justice system at such a young age can lead to a higher likelihood of future criminal activity.

Further complications arise as Queensland already harbors the highest number of children in detention facilities compared to other Australian states, leading to concerns that more minors may be held in police cells for extended periods due to overcapacity in detention centers. Promises of future investments in detention alternatives have been made, yet immediate implications on vulnerable youth and the judicial process remain a pressing concern. As this debate unfolds, the long-term effectiveness of these laws continues to be scrutinized against mounting evidence opposing punitive measures as solutions to youth crime.