Earlier this month, a Palestinian diplomat, called Husam Zomlot, was invited to a discussion at the Chatham House think tank in London. Belgium had just joined the UK, France and other countries in promising to recognize a Palestinian state at the United Nations in New York. Dr Zomlot, Head of the Palestinian Mission to the UK, was clear that this was a significant moment. What you will see in New York might be the actual last attempt at implementing the two-state solution, he warned. Let that not fail.

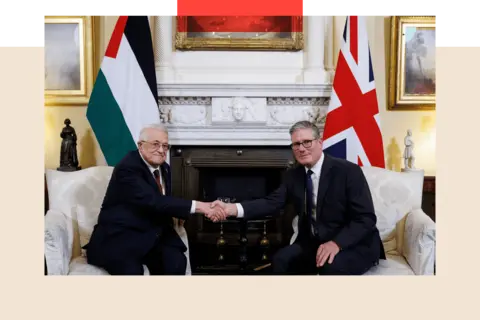

Weeks on, that has now come to pass. The UK, Canada and Australia, who are all traditionally strong allies of Israel, have now taken this step. Sir Keir Starmer announced the UK's move in a video posted on social media. In it he said: In the face of the growing horror in the Middle East, we are acting to keep alive the possibility of peace and of a two-state solution. That means a safe and secure Israel alongside a viable Palestinian state - at the moment we have neither.

More than 150 countries had previously recognized a Palestinian state, but the addition of the UK and the other countries is seen as a significant moment. Palestine has never been more powerful worldwide than it is now, says Xavier Abu Eid, a former Palestinian official. The world is mobilized for Palestine. But there are complicated questions to answer, including what is Palestine and is there even a state to recognize?

Four criteria for statehood are listed in the 1933 Montevideo Convention. Palestine can justifiably lay claim to two: a permanent population (although the war in Gaza has put this at enormous risk) and the capacity to enter into international relations - Dr Zomlot is proof of the latter. But it doesn't yet fit the requirement of a defined territory. With no agreement on final borders and no actual peace process, it's difficult to know with any certainty what is meant by Palestine.

For the Palestinians themselves, their longed-for state consists of three parts: East Jerusalem, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. All were conquered by Israel during the 1967 Six Day War. The West Bank and Gaza Strip have been geographically separated by Israel for three quarters of a century, since Israel's independence in 1948.

In the West Bank, the presence of the Israeli military and Jewish settlers means the Palestinian Authority, established after the Oslo Accords peace deals of the 1990s, administers only around 40% of the territory. Since 1967, the expansion of settlements has eaten away at the West Bank, breaking it up into an increasingly fragmented political and economic entity. Meanwhile, East Jerusalem, which Palestinians regard as their capital, has been ringed with Jewish settlements, gradually cutting off the city from the West Bank. Gaza's fate, of course, has been much worse; after almost two years of war, much of the territory has been obliterated.

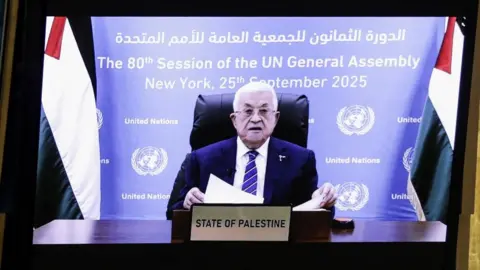

Back in 1994, an agreement between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) led to the creation of the Palestinian National Authority (known simply as the Palestinian Authority or PA), which exercised partial civil control over Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. But since a bloody conflict in 2007 between Hamas and the main PLO faction Fatah, Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank have been ruled by two rival governments: Hamas in Gaza and the internationally recognized Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, whose president is Mahmoud Abbas.

Despite the leadership on paper, Palestinian politics has ossified. The last presidential and parliamentary elections were in 2006, meaning that no Palestinian under the age of 36 has ever voted in the West Bank or Gaza. This stagnation has left many disillusioned, with calls for a new leadership growing louder as the situation in Gaza deteriorates.

Even with recognition from various nations, many question if the empowerment of Palestine will lead to a coherent leadership capable of managing the complexities of a new state. While many voices point to Barghouti as a potential leader, he remains imprisoned, challenging the hope for a united Palestinian leadership moving forward. As international dialogue continues, the pressing need remains to first address the humanitarian crisis that plagues the region.

The question stands: is the symbolism of recognition enough to pave the way for tangible progress towards peace and Palestinian statehood?

Weeks on, that has now come to pass. The UK, Canada and Australia, who are all traditionally strong allies of Israel, have now taken this step. Sir Keir Starmer announced the UK's move in a video posted on social media. In it he said: In the face of the growing horror in the Middle East, we are acting to keep alive the possibility of peace and of a two-state solution. That means a safe and secure Israel alongside a viable Palestinian state - at the moment we have neither.

More than 150 countries had previously recognized a Palestinian state, but the addition of the UK and the other countries is seen as a significant moment. Palestine has never been more powerful worldwide than it is now, says Xavier Abu Eid, a former Palestinian official. The world is mobilized for Palestine. But there are complicated questions to answer, including what is Palestine and is there even a state to recognize?

Four criteria for statehood are listed in the 1933 Montevideo Convention. Palestine can justifiably lay claim to two: a permanent population (although the war in Gaza has put this at enormous risk) and the capacity to enter into international relations - Dr Zomlot is proof of the latter. But it doesn't yet fit the requirement of a defined territory. With no agreement on final borders and no actual peace process, it's difficult to know with any certainty what is meant by Palestine.

For the Palestinians themselves, their longed-for state consists of three parts: East Jerusalem, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. All were conquered by Israel during the 1967 Six Day War. The West Bank and Gaza Strip have been geographically separated by Israel for three quarters of a century, since Israel's independence in 1948.

In the West Bank, the presence of the Israeli military and Jewish settlers means the Palestinian Authority, established after the Oslo Accords peace deals of the 1990s, administers only around 40% of the territory. Since 1967, the expansion of settlements has eaten away at the West Bank, breaking it up into an increasingly fragmented political and economic entity. Meanwhile, East Jerusalem, which Palestinians regard as their capital, has been ringed with Jewish settlements, gradually cutting off the city from the West Bank. Gaza's fate, of course, has been much worse; after almost two years of war, much of the territory has been obliterated.

Back in 1994, an agreement between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) led to the creation of the Palestinian National Authority (known simply as the Palestinian Authority or PA), which exercised partial civil control over Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. But since a bloody conflict in 2007 between Hamas and the main PLO faction Fatah, Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank have been ruled by two rival governments: Hamas in Gaza and the internationally recognized Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, whose president is Mahmoud Abbas.

Despite the leadership on paper, Palestinian politics has ossified. The last presidential and parliamentary elections were in 2006, meaning that no Palestinian under the age of 36 has ever voted in the West Bank or Gaza. This stagnation has left many disillusioned, with calls for a new leadership growing louder as the situation in Gaza deteriorates.

Even with recognition from various nations, many question if the empowerment of Palestine will lead to a coherent leadership capable of managing the complexities of a new state. While many voices point to Barghouti as a potential leader, he remains imprisoned, challenging the hope for a united Palestinian leadership moving forward. As international dialogue continues, the pressing need remains to first address the humanitarian crisis that plagues the region.

The question stands: is the symbolism of recognition enough to pave the way for tangible progress towards peace and Palestinian statehood?