Since his release from a Russian prison, Dmytro Khyliuk has barely been off the phone. The Ukrainian journalist was detained by Russian forces in the first days of their full-scale invasion. Three and a half years later he's been released in a prisoner swap, one of eight civilians freed in a surprise move. While Russia and Ukraine have swapped military prisoners of war before, it is very rare for Russia to release Ukrainian civilians. Dmytro has been catching up frantically on all he's missed. But he's also phoning the families of every Ukrainian he met in captivity: he memorised all their names and each detail.

He knows that for some, his call may be the first confirmation that their relative is alive.

There were celebrations here last month when Dmytro was returned from Russia in a group of 146 Ukrainians. A crowd came out waving blue and yellow national flags, cheering as the buses carrying the freed men passed hooting their horns. Most on board were soldiers with sunken cheeks, emaciated after their years behind bars. Officials won't say exactly how they got the eight Ukrainian civilians back in the same exchange, only that it involved sending back in return people Russia was interested in.

One source said those included residents of the Kursk region in Russia, evacuated when Ukrainian forces launched their 2024 incursion. The group's exact status after that is unclear.

Stepping off the bus to a cheering crowd, Dmytro's first phone call was to tell his mother he was free. Both his parents are elderly and unwell, and his greatest fear had been never seeing them again. The hardest was not knowing when you'll be allowed back. You could be freed the next day or stay prisoner for 10 years. Nobody knows how long it's for.

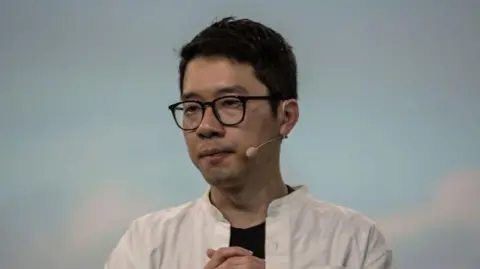

We met Dmytro shortly after his release as he recuperated at a Kyiv hospital. The details he shared of his captivity are chilling. They grabbed us and literally dragged us to the prison and on the way they beat us with rubber batons shouting things like, 'How many people have you killed? He was held in multiple facilities and his account chimes with many others we've heard over the years. Sometimes they'd let the guard dog off its leash so that it could bite us. The cruelty was really shocking and it was constant.

Physically the first year was the hardest. We were starving. We were given very little food for a long time, he remembers. He lost more than 20kg in the first few months, causing him dizzy spells. But the soldiers he was held with were treated far worse. The journalist was never charged with any crime.

The journalist's family home is a world away from all that, in the pretty village of Kozarovychi just outside Kyiv. It feels peaceful, apart from the air raids, with gardens full of poultry, blackberry bushes, and fruit trees. But the back wall of Dmytro's house still has chunks torn out of it by shrapnel, and the lawn was only just repaired where Russian troops had parked a tank. In 2022, right at the start of their full-scale invasion when the Russians were advancing on Kyiv, they took over the village.

Dmytro's parents, Halyna and Vasyl, now live with an enduring fear for their son and other missing civilians. Across Ukraine, officials say more than 16,000 civilians are currently missing. Dmytro Lubinets, Ukraine's human rights ombudsman, describes dealing with Russia as like playing chess, where Ukraine is at a disadvantage. As Dmytro prepares to return home to start a new chapter, he mentioned how different the country feels now amidst ongoing conflict.\

He knows that for some, his call may be the first confirmation that their relative is alive.

There were celebrations here last month when Dmytro was returned from Russia in a group of 146 Ukrainians. A crowd came out waving blue and yellow national flags, cheering as the buses carrying the freed men passed hooting their horns. Most on board were soldiers with sunken cheeks, emaciated after their years behind bars. Officials won't say exactly how they got the eight Ukrainian civilians back in the same exchange, only that it involved sending back in return people Russia was interested in.

One source said those included residents of the Kursk region in Russia, evacuated when Ukrainian forces launched their 2024 incursion. The group's exact status after that is unclear.

Stepping off the bus to a cheering crowd, Dmytro's first phone call was to tell his mother he was free. Both his parents are elderly and unwell, and his greatest fear had been never seeing them again. The hardest was not knowing when you'll be allowed back. You could be freed the next day or stay prisoner for 10 years. Nobody knows how long it's for.

We met Dmytro shortly after his release as he recuperated at a Kyiv hospital. The details he shared of his captivity are chilling. They grabbed us and literally dragged us to the prison and on the way they beat us with rubber batons shouting things like, 'How many people have you killed? He was held in multiple facilities and his account chimes with many others we've heard over the years. Sometimes they'd let the guard dog off its leash so that it could bite us. The cruelty was really shocking and it was constant.

Physically the first year was the hardest. We were starving. We were given very little food for a long time, he remembers. He lost more than 20kg in the first few months, causing him dizzy spells. But the soldiers he was held with were treated far worse. The journalist was never charged with any crime.

The journalist's family home is a world away from all that, in the pretty village of Kozarovychi just outside Kyiv. It feels peaceful, apart from the air raids, with gardens full of poultry, blackberry bushes, and fruit trees. But the back wall of Dmytro's house still has chunks torn out of it by shrapnel, and the lawn was only just repaired where Russian troops had parked a tank. In 2022, right at the start of their full-scale invasion when the Russians were advancing on Kyiv, they took over the village.

Dmytro's parents, Halyna and Vasyl, now live with an enduring fear for their son and other missing civilians. Across Ukraine, officials say more than 16,000 civilians are currently missing. Dmytro Lubinets, Ukraine's human rights ombudsman, describes dealing with Russia as like playing chess, where Ukraine is at a disadvantage. As Dmytro prepares to return home to start a new chapter, he mentioned how different the country feels now amidst ongoing conflict.\