The murder of an interfaith couple and the arrest of the woman's brothers by the police for the alleged crime has shocked a small village in India's northern Uttar Pradesh state where residents have lived in harmony for years.

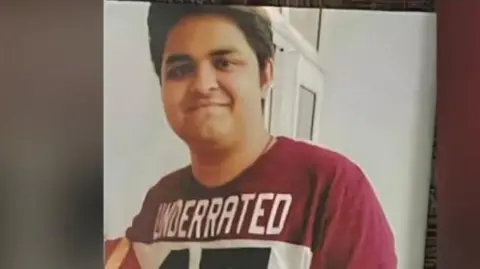

The bodies of 19-year-old Kajal, a Hindu, and 27-year-old Mohammad Arman, a Muslim, were found buried near a riverbank on the outskirts of Umri village on 21 January.

Police said they were beaten to death with a spade two days earlier, allegedly by Kajal's three brothers, who have been arrested. They are in custody and have not commented on the killings.

The murders have left an uneasy quiet hanging over Umri, 182km (113 miles) from India's capital Delhi. The village is home to about 400 families - from both Hindu and Muslim communities - and several residents told the BBC that they have shared a warm relationship without any history of religious disputes.

Deputy inspector general of state police Muniraj G told the BBC that police believe it to be a case of honour killing - murder by relatives or community members to punish women for falling in love or marrying outside of their caste or religion.

India's National Crime Records Bureau began recording honour killings in 2014, when it listed 18 cases nationwide. Its latest annual report recorded 38 such cases in 2023. Activists, however, say the numbers are significantly higher - in hundreds every year - as many cases are recorded simply as homicide.

Umri is in Uttar Pradesh's Moradabad district, which is known for its metal craft industries. The region is largely rural, where strong social hierarchies continue to influence everyday life. Kajal's brothers worked as masons in Moradabad town.

Kajal and Arman's relationship was the first case [of an interfaith relationship] in their village, says resident Mahipal Saini.

Residents of Umri who spoke to the BBC on condition of anonymity said Kajal and Arman were neighbours who lived hardly 200m from each other. They described them as introverts who did not have many friends.

Kajal taught at a private school in Umri, while Arman had returned to the village about five months ago after spending four years in Saudi Arabia where he worked at a food outlet. His relatives said he came back as he didn't earn much there and had been working with a local stone-crushing contractor since his return.

The murders allegedly took place in Kajal's house on the intervening night of 18 and 19 January, when her brothers caught Arman visiting her. The brothers - Rajaram, Satish and Rinku Saini - are in jail and have not said anything in their defence so far.

Their father, Ganpat Saini, told the BBC that he and his wife were not at home at the time of the murders. He said they were sleeping in a shed on the outskirts of the village where they usually spend nights to guard their livestock. He added that he was grieving his daughter.

Arman's elder brother Farman Ali said that his brother left home after dinner on 18 January, saying he would be back with some medicines for their parents. When he hadn't returned by the next morning and his phone was switched off, his family started panicking and went to the police. This led to a search operation in the village.

Police allege that Kajal's brothers attempted to mislead them by lodging a missing complaint about her on 20 January, accusing Arman of abducting her.

Further investigation led them to the spot where the bodies were buried, police said. Ganpat Saini says that when he and his wife returned home on the morning of 19 January, they could not find Kajal at home. He says he learnt about the murder only after the bodies were found.

However, he did not answer when asked whether he or anyone in his family knew that Kajal and Arman were in a relationship. Arman's family say they were unaware of his relationship with Kajal.

Villagers say they usually resolve disputes with help from elected village council leaders. If the family [of Kajal] had acted more reasonably, the elders in the village could have helped resolve it, says villager Mahipal Saini.

Police say they have deployed personnel to ensure there is no religious violence. And villagers say their lives are slowly returning to routine, although the killings have forced an uneasy reflection.

We never imagined something like this could happen here, says Arif Ali, another Umri resident. It's not that men and women in the village have suddenly started feeling unsafe. But there is a silence that hangs over us.

The Umri murders join the long list of suspected honour killing cases reported from across India over decades. More than 93% of marriages in India are arranged by families within their own caste and faith, and couples who deviate from the tradition are routinely forced to seek protection from police or courts.

Indian law regards honour killings as murder, and courts have repeatedly affirmed that an adult's choice of partner by consent is constitutionally protected. Yet cases of violence continue to be reported from across states.