At a bus stand in the northern Indian city of Lucknow, the anxious faces tell their own story. Nepalis who once came to India in search of work are now hurrying back across the border, as the nation reels with its worst unrest in decades. We are returning home to our motherland, says one man. We are confused. People are asking us to come back. Earlier this week, Nepal's Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli quit after 30 died in clashes triggered by a social media ban. While the ban was later reversed, Gen Z-led protests raged on. A nationwide curfew is in place, soldiers patrol the streets, and parliament and politicians' homes have been set ablaze. With Oli gone, Nepal has no government in place.

For migrants like Saroj Nevarbani, the choice is stark. There's trouble back home, so I must return. My parents are there - the situation is grave, he told BBC Hindi. Others, like Pesal and Lakshman Bhatt, echo the uncertainty. We know nothing, they say, but people at home have asked us to come back. For many, the journey back is not just about wages or work - it is bound up with family ties, insecurity, and the rhythms of migration that have long shaped Nepali lives. Nepalis in India, after all, fall broadly into three groups.

The first group includes migrants who leave families behind to work as cooks, domestic helpers, security guards, or in low-paid jobs across Indian cities. They remain Nepali citizens, move back and forth without Aadhaar (India's biometric identity card), and are often denied basic services, which is why they are sometimes referred to as seasonal migrants. The second group consists of those who relocate with their families, build lives in India, and often obtain identity cards, yet retain Nepali citizenship and ties to home, even returning to vote. Finally, there are Indian citizens of Nepali ethnicity - descendants of earlier migrations between the 18th to 20th centuries - who are rooted in India but still claim cultural kinship with Nepal.

Nepal also tops the list of foreign students in India, with more than 13,000 out of some 47,000, according to the latest official data. Many other Nepalese cross the 1,750 km (466 miles) open border for medication, supplies, or family visits, eased by a 1950 peace and friendship treaty and strong social networks.

New Nepali migrants entering India's labor market are typically 15–20 years old, though the overall median age is 35, according to Keshav Bashyal of Kathmandu's Tribhuvan University. Joblessness and rising inequality drive migration, especially among the poor, rural, and less educated, whose labor force participation is already low. Most come from poorer backgrounds, working in construction and religious sites in Uttarakhand, on farms in Punjab, in factories in Gujarat, and in hotels across Delhi and beyond, Dr. Bashyal told me. This steady flow of young migrants feeds into a sizable, though largely invisible, workforce in India.

The sheer number of Nepali citizens engaging in labor within India is challenging to determine due to the open border, but estimates suggest around 1-1.5 million. Nepal's reliance on its migrants is staggering, with remittances accounting for a significant portion of the country's GDP and household income. For example, in 2016-2017, remittances made up over a quarter of Nepal's GDP, which by 2024 accounted for 27–30%. Over 70% of households receive such remittances, indicating their crucial importance.

While these migrants play an essential role in sustaining their families back home, they often face precarious living conditions in India. A 2017 study indicated that they frequently reside in squalid conditions, experiencing discrimination at work and in healthcare settings. Despite the socio-economic challenges, especially evident for those working in low-status jobs, some migrants do manage to prosper, particularly those who venture beyond India to seek employment in more developed regions.

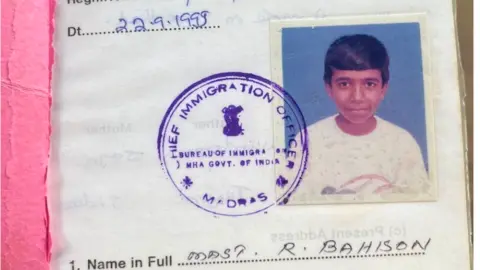

Dhanraj Kathayat, a security guard in Mumbai who arrived in India in 1988, exemplifies the struggles many face. Despite nearly three decades in India, his economic mobility remains limited. His story underscores the perpetual cycle of migration induced by economic pressures and the ongoing need for survival.

Looking to the future, analysts suggest that ongoing political unrest in Nepal will only exacerbate emigration trends, pushing even more young individuals towards India's informal economy, where jobs are available but often come with little security.